The Real Religious Hubris Is Not Theosis

Lincoln Cannon

6 June 2010 (updated 3 January 2026)

Transhumanists have been charged with hubris: the arrogance of playing God. As the argument goes, our aspirations are beyond moral bounds, our trust in human ability is unwarranted and dangerous, and we may even risk the wrath of some God that would punish us to rectify our attitude and put us in our proper place as his lowly creatures.

The standard Transhumanist response to this charge is that humans have always been playing God, and indeed it is the essence of humanity to play God. In that first moment when one of our ancestors picked up a stone to defend herself, rather than allow “nature” to take its course, she was playing God – plucking fruit from the tree of knowledge, as it were. Those who fly in airplanes, communicate through computers, and transplant hearts are playing God still. Those who would cure cancer or explore Mars are yet intending to play God for some time to come.

From a Biblical perspective, we were invited to play God from the beginning. “God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness” (Genesis 1: 26). The psalmist elaborated, “Ye are gods; and all of you are children of the most High” (Psalm 82: 6). Jesus confirmed, “Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods?” (John 10: 34).

Many early Christians embraced this concept. Athanasius declared, “God became man that man become God” (Incarnation of the Word of God 54: 3). Irenaeus agreed, “If the Word became a man, it was so men may become gods” (Against Heresies 5). Clement of Alexandria further reasoned, “if one knowns himself, he will know God, and knowing God will become like God” (The Instructor 3: 1). And Origen encouraged, “Men should escape from being men, and hasten to become gods” (Commentary on John 29: 27).

Inheriting from those Christians, Mormons have celebrated this idea of theosis (man becoming God). Joseph Smith taught early Mormons that we “have got to learn how to be gods” (Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith 346) and that we are called “to be the saviors of men” (Doctrine and Covenants 103: 9). And, to be sure, this was not merely a passive or exclusively ritualistic advocacy. The Book of Mormon reminded the early Mormons that God would not deliver us if we do not make use of the means provided (Alma 60: 20-23). The Lectures on Faith asserted that faith in God is a matter of emulation and a principle of action (Lecture First, Section I, 7-11). And Joseph Smith even went so far as to teach, “After this instruction, you will be responsible for your own sins; it is a desirable honor that you should so walk before our heavenly Father as to save yourselves; we are all responsible to God for the manner we improve the light and wisdom given by our Lord to enable us to save ourselves” (History of the Church 4: 606).

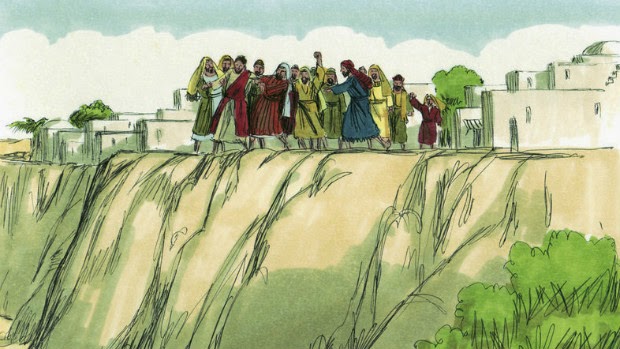

What, then, should we make of these charges of hubris, typically expressed by other religious persons? When they charge us with arrogance and unjustified pride, I am reminded of the Pharisees, who perceived Jesus as a threat to their power. With Jesus, even at his invitation, some of us advocate unity with God through emulation and eventual full immersion in that identity (John 17: 20-23). Like Jesus, we think it not robbery to become equal with the God whose form we share (Philippians 2: 6). Others, with the Pharisees, would stone us as blasphemers (John 10: 31-39).

Where, actually, is the arrogance in this matter? Who thinks he knows the limits to the knowledge and power of humanity? Who claims to be the gatekeeper on our relationship with God? Who prefers unknowable mysteries that disenfranchise all those outside the inner circle? Who thinks himself more holy and worthy consequent to exclusive ceremonial access? Who, actually, is the appropriate target for charges of hubris?

Jesus identified the appropriate target in these words: “But woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye shut up the kingdom of heaven against men: for ye neither go in yourselves, neither suffer ye them that are entering to go in” (Matt 23: 13).

Mormon prophet Ezra Benson identified the appropriate target for charges of arrogance in these words: “My dear brethren and sisters, we must prepare to redeem Zion. It was essentially the sin of pride that kept us from establishing Zion in the days of the Prophet Joseph Smith … Pride is the great stumbling block to Zion. I repeat: Pride is the great stumbling block to Zion. We must cleanse the inner vessel by conquering pride.”

These strong words were not directed at the non-religious. To the contrary, these words were aimed at persons like me, raised and educated in a religious culture and endowed with religious authority that too often influences us to think ourselves better than others for reasons that, ironically, actually make us worse than others.

In a moment of divine inspiration, Joseph Smith taught, “We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion” (Doctrine and Covenants 121: 39). Such persons begin to establish creeds and dogmas that would separate us from God, declaring, “Hitherto shalt thou come, and no further.” Then, further to solidify their power by increasing the dependency on their authority, they articulate their creeds and dogmas in words that no one can understand (Jacob 4: 14). They appeal to unknowlable mysteries, unreproducible experiences, and incomprehensible gods. They encourage ignorance and impotence, and prepare the downfall and damnation of their people.

Hubris, then, is not in our common aspiration, as children of God, to become as God. Rather, hubris is in the egotistical aspirations of those who would stand in our way for their own temporary gain. Arrogance is not in attempting the good old fashioned work that leads to desired results. Rather, arrogance is in the passive thought that your God will save you despite your efforts.

The God in which I put my faith would have us share in that glory (Romans 8: 17), speaks according to our language (Doctrine and Covenants 1: 24-28), reasons among us according to our understanding (Doctrine and Covenants 50: 10-12), withholds no knowledge (Doctrine and Covenants 121: 26-33), and invites us to greater works (John 14: 12). To the extent that we, Transhumanists, think ourselves capable of attaining such glory independent of opportunity provided by God, we are indeed guilty of hubris. Yet more guilty, however, are those who engage in the religious hubris and hypocrisy of raising themselves above God when seeking to prevent others from acting on opportunity.