American Atheists

Lincoln Cannon

21 April 2014 (updated 3 January 2026)

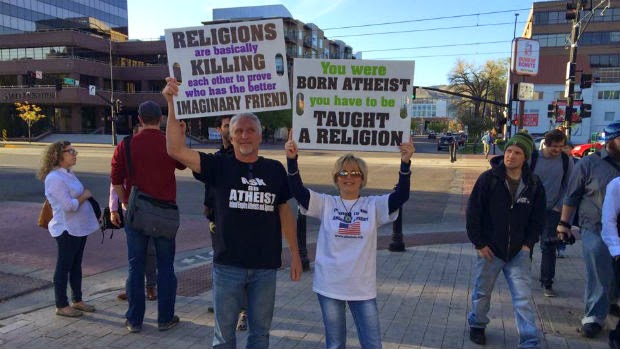

Last week, I encouraged the Mormon Transhumanist Association (MTA) to sponsor recording of a panel discussion between Mormons and atheists, sponsored by the American Atheists (AA) and held at the Salt Lake City Public Library as part of its annual convention. The MTA leadership team agreed. And the recording is now available on the association’s YouTube channel (along with a lot of other thought provoking content).

Since that time, I’ve received many requests regarding my thoughts on the American Atheists. So I thought I would compose a review of their stated “aims and principles.”

“American Atheists, Inc. is a nonprofit, nonpolitical, educational organization dedicated to the complete and absolute separation of state and church, accepting the explanation of Thomas Jefferson that the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States was meant to create a ‘wall of separation’ between state and church.”

Judging from statements by David Silverman, President of AA, during the panel discussion between Mormons and atheists, I’m not at all sure I understand what AA really intends us to understand by “complete and absolute separation of state and church.” He made several alarming statements promoting the eradication of religion. If that’s what AA aims for, of course I disagree completely on this issue.

On the other hand, if David was simply engaging in (arguably irresponsible) hyperbole, and if AA really only stands for separation of sectarian religion from state governance, as would seem to correspond with the appeal to Thomas Jefferson, I completely agree. I don’t want to live in a state governed by any sectarian religion, and I’m pretty confident most of us don’t.

I qualify “religion” with “sectarian” simply because I hold that the religious phenomenon manifests itself more broadly than we generally acknowledge, even in the sectarian emotional marketing of AA and in the ecumenical patriotism encouraged by the USA, and that something like an ecumenical religion may be essential to the deepest esteem for governance, nothing short of which would be necessary for perpetuating governance through times of crisis.

“American Atheists, Inc., is organized to stimulate and promote freedom of thought and inquiry concerning religious beliefs, creeds, dogmas, tenets, rituals, and practices;”

I support this. Unfortunately, in my own religious tradition of Mormonism, we haven’t always practiced this as much as we should have. And we still don’t, although I do think there are many reasons, beyond the scope of this post, to suppose we’re improving.

“… to collect and disseminate information, data, and literature on all religions and promote a more thorough understanding of them, their origins, and their histories;”

I support this. I doubt AA actually does this in a holistic way. My impression is that it does so in a biased way, as illustrated by David, who explicitly describes religion as “evil.” While there is most certainly evil in the history of religion, we can claim, quite objectively, that there is most certainly good in the history of religion. Even the softer claim that religion is evil on the whole is highly controversial at best. If David’s attitude is representative of AA members generally, they are doing themselves no service, on the one hand appealing to reason and on the other making indiscriminate and careless moral claims regarding the history of religion. It seems abundantly clear to me that religion is a powerful social technology that can be and has been used for great evil and great good, and, as with all technologies, it’s up to us to channel its power toward good while working to mitigate its evil applications.

“… to advocate, labor for, and promote in all lawful ways the complete and absolute separation of state and church;”

I might support this. As mentioned at the beginning of this post, I support the separation of state and sectarian religion, but I disagree with the idea that religion should be eradicated, which is a position David claims to hold and which I fear many members of AA probably hold. Ironically such an antireligious position itself manifests the fundamentalist instinct, often expressed with nothing short of a religious vitriol.

“… to advocate, labor for, and promote in all lawful ways the establishment and maintenance of a thoroughly secular system of education available to all;”

I support this. In fact, I would take this even further or at least emphasizing a specific aspect of this more by advocating the establishment and maintenance of a thoroughly secular system of scientific education available to all. Too often religion (occasionally including atheist religion, albeit far less frequently than mainstream religion) becomes part of our science classes. It’s the wrong place for religion to appear in school, unless it happens to be social science classes that study religion from a thoroughly secular perspective.

“… to encourage the development and public acceptance of a humane ethical system stressing the mutual sympathy, understanding, and interdependence of all people and the corresponding responsibility of each individual in relation to society;”

I support this. In fact, such matters are essential to my sense of morality, although I would also extend the system to responsibilities in relation to the environment. Some religious persons would appeal uniquely to God for their sense of morality. However, many if not most Mormons recognize laws applicable even to God. While we might not all agree on the details of what those laws are, it would be a mistake to assume, as I heard David claim during the Mormon and atheist panel, that theists rely uniquely on appeals to authority. It’s more complicated than that, as the work of Jonathan Haidt illustrates.

“… to develop and propagate a social philosophy in which humankind is central and must itself be the source of strength, progress, and ideals for the well-being and happiness of humanity;”

I do not support this. While I certainly would support the idea that humanity should be A source of strength, progress and ideals, I cannot reasonably imagine humanity to be THE source of strength, progress and ideals, and I simply don’t share in the esthetic of human centrality. Such strikes me as human racism and anti-environmentalism – an arrogant or ignorant positioning of humanity in relation to our world. Along with terrible risks, our world presents us with wonderful opportunities. While human ingenuity and strength are essential to pursuing and realizing those opportunities, we would not exist, survive or thrive without the opportunities themselves. Even when directed at a world perceived as merely inanimate, gratitude is an empowering principle. Moreover, as a Transhumanist, I feel a moral obligation to look both in and beyond humanity for moral worth, projecting it on our nonhuman cousins, on our artificial and posthuman descendants, and on any extraterrestrial intelligences that may exist, world creators and otherwise. Basically, this AA principle is a Humanism that is a good start and yet insufficient for my Transhumanism.

“Atheism may be defined as the mental attitude which unreservedly accepts the supremacy of reason and aims at establishing a life-style and ethical outlook verifiable by experience and scientific method, independent of all arbitrary assumptions of authority and creeds.”

I suspect many atheists would disagree with this definition. It does distinguish me, squarely, as not being an atheist because I don’t accept the supremacy of reason. While I do accept reason as an important tool, I do not accept it as supreme. Frankly, I doubt many if any members of AA actually accept the supremacy of reason either. Rather, like me, they almost certainly have underlying esthetic motivators for embracing reason as an important tool. Truth in itself is not inherently good. Truth in itself is not inherently beautiful. I care about truth, but I care far more for good and beautiful truth than evil and ugly truth. To the extent the truth is evil and ugly, I would acknowledge and work to change it for the better and more beautiful. To the extent the truth is good and beautiful, I would embrace and celebrate it. An important kind of truth is created, and an important kind of created truth depends on our working trust in its possibility. Such working trust is perfectly compatible with a pancritical rationalism.

That aside, I share with AA the aim of establishing a lifestyle and ethical outlook verifiable by experience and scientific method, to the extent practical. Of course it’s not practical (and it’s probably not even possible) in any exhaustible sense. Although science can and should surely extend its reach indefinitely, ever more deeply informing our ethics and esthetics in a feedback loop, it is always incomplete. Confronted with the real demands of life, particularly at its most vital moments, we must act, often prematurely insofar as science is concerned.

I like how AA places “arbitrary assumptions” as a qualifier on authority and creeds, and I feel that my perspective on authority and creeds would resonate with theirs. When it comes to authority, I recognize limited value in the authority of control and limitless value in the authority of influence, particularly the influence of compassion. To the extent authority or creeds are established on anything other than the influence of compassion, their power will be limited at best to their relative strength, whereas the authority that arises naturally from compassionate influence will endure as long as the minds that experience it.

“Materialism declares that the cosmos is devoid of immanent conscious purpose; that it is governed by its own inherent, immutable, and impersonal laws; that there is no supernatural interference in human life; that humankind – finding their resources within themselves – can and must create their own destiny.”

This is incorrect. Materialism does not declare, and the cosmos is not devoid of immanent conscious purpose. Materialism, in itself, is simply a philosophical position contrasted with idealism or dualism, positing that everything is physical, as opposed to everything being mental. Presumably, all philosophical materialists must confront the brute fact of their own conscious purposes as part of the cosmos, and almost all would charitably extend conscious purposes well beyond themselves to at least other humans, if not beyond humans. It’s not particularly controversial to claim that at least parts of the cosmos have immanent conscious purposes.

These conscious purposes also give rise to new laws, first socially and then even environmentally, as we engineer environments according to our purposes. We even go so far as to create physics engines for virtual worlds that, although embedded in laws that we appear unable to change at least at present, can present entirely different laws to everything within their sphere of influence.

Whether the broadest cosmic laws discovered by science are inherent and immutable and impersonal, science itself cannot say. Rather than proving immutability, science usually assumes temporal and spatial uniformity, and can only ever prove them to limited extents within the constraints of other assumptions. Some scientists actively question whether the discovered laws of our observed universe are inherent or whether they might vary in other universes. Moreover, if something like the Simulation Hypothesis is true, our universe may be embedded in a posthuman intelligence and be very personal indeed.

I do happen to share with AA the position that there are no supernatural interferences in human life, but I do so on philosophical and pragmatic grounds – not scientific, to be sure. Even if I could make sense of the proposed distinction between natural and supernatural, which I haven’t, I would still see little practical value in attributing anything to supernatural causes because doing so would needlessly end the scientific project on an assumption rather than a conclusion. So far as I’m concerned, even God becomes God through natural means, suggesting how we might do the same.

“Materialism restores dignity and intellectual integrity to humanity.”

This is a strange claim. While I happen to identify as a materialist of sorts (as do most Mormons, whose scriptures describe spirit as matter and God as embodied), I don’t see how such in itself restores human dignity or intellectual integrity. Idealists such as George Berkeley seem to have, at least arguably, reasonable grounds for associating their positions with human dignity and intellectual integrity too. That said, if someone can persuade me that philosophical materialism is essential to human dignity and intellectual integrity, I would be happy to embrace the idea. I have nothing against materialism, except to the extent that some would gloss over the problem of consciousness, for which we simply don’t yet have a good scientific solution (and which tentatively inclines me to something of a panpsychism).

“It teaches that we must prize our life on earth and strive always to improve it. It holds that human beings are capable of creating a social system based on reason and justice.”

Even if materialism teaches these things, which I see no reason to suppose it does in itself, many non-materialist philosophies do as well.

“Materialism’s ‘faith’ is in humankind and their ability to transform the world culture by their own efforts.”

While I share and even celebrate a limited faith in humanity, it’s not my materialism that leads me to this, nor do I think such faith sufficient in itself. While we should certainly love and trust in each other as we are to some extent, we should also look higher and farther, loving and trusting in the radically compassionate and creative posthumanity that we can and should become. I call such posthumanity “God,” and to the extent of its compassionate and creative capacities, I call it “Christ,” as exemplified by Jesus, who invites us to be one with him in Christ, becoming radically compassionate creators together. In my estimation, nothing else is more worthy of my faith.

“This is a commitment which is in its very essence life-asserting.”

While the AA commitment does sound life-asserting to some extent, it yet sounds relatively pessimistic. If God is life-affirming posthumanity, compassionate and creative even to resuscitative redemption of its past, atheism is pessimism. It might go so far as a human (all too human?) flourishing, but would it go so far as a posthuman flourishing? Would it embrace the flourishing of natural Godhood? Could it see, beyond its antireligious dogmatism, the heights of life-affirmation in resuscitative redemption of our past? Would it too hastily reject mechanisms such as cryonics, plastination, quantum archeology and ancestor simulations, while there is yet scientific room for hope? If not, it’s ultimately a pessimism.

“It considers the struggle for progress as a moral obligation that is impossible without noble ideas that inspire us to bold, creative works. Materialism holds that our potential for good and more fulfilling cultural development is, for all practical purposes, unlimited.”

While materialism doesn’t necessarily entail these ideals, I enthusiastically share them, so much so that I wonder whether AA should give up its Humanism and replace it with Transhumanism. Humanity is not the end of evolution, and we are increasingly taking control of our own evolution. Perhaps we will survive and thrive to radical flourishing in compassion and creation? Perhaps we will become like God? Indeed, perhaps “god-like” beings already exist, as Richard Dawkins supposes. In any case, as the New God Argument shows, we have moral and practical reasons to trust in the existence of natural Gods because our probable future correlates with their probable present. Their present limits are our future limits. Is our potential for good and more fulfilling cultural development really, as AA supposes for all practical purposes, unlimited? I hope so.