This Is Still the Place

Lincoln Cannon

24 July 2014 (updated 3 January 2026)

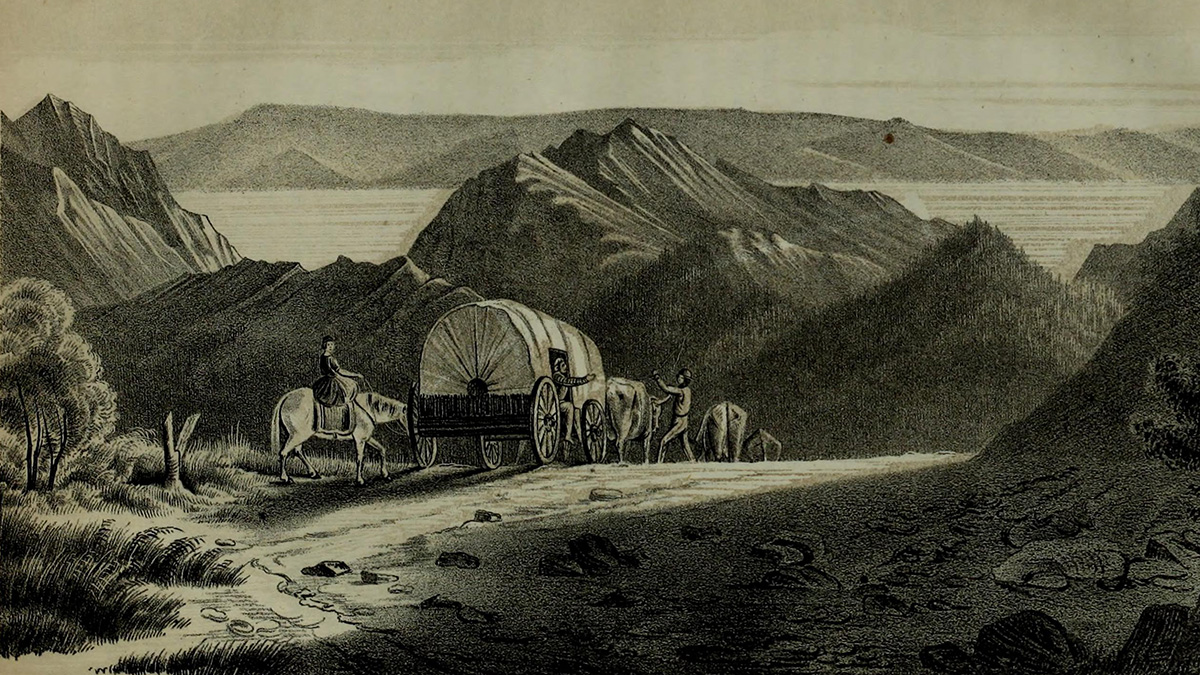

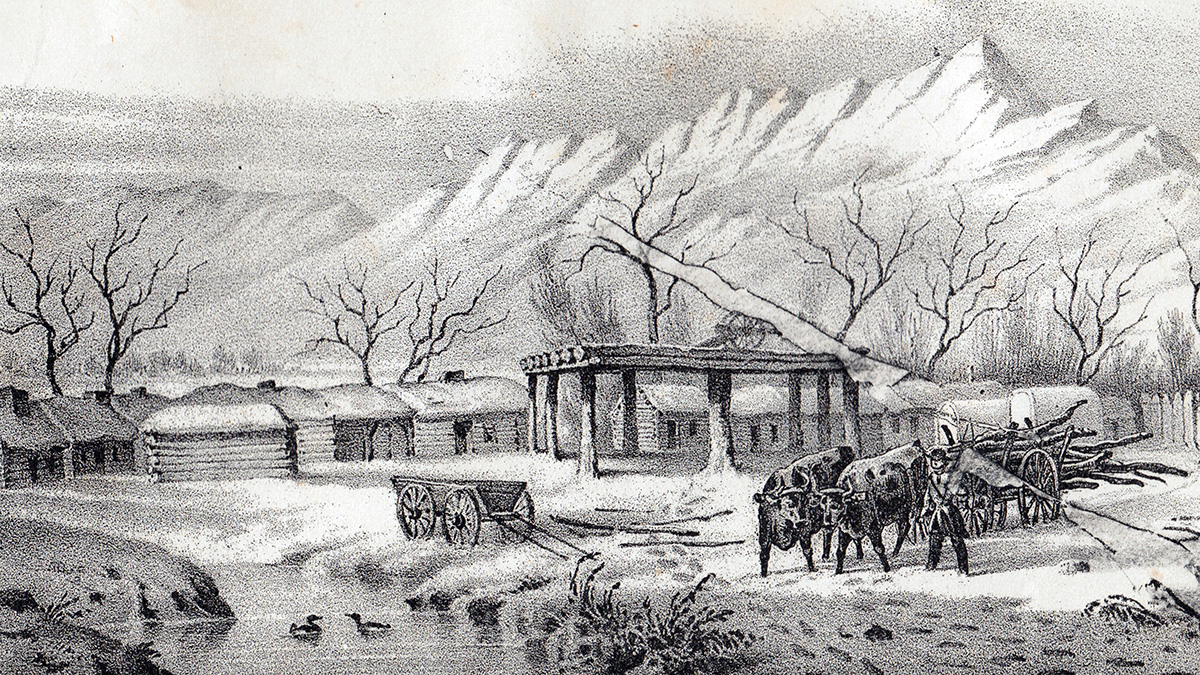

On the morning of 24 July 1847, a group of Mormon pioneers broke camp for the last time. They traveled six miles through a deep ravine, across one last creek, and into full view of a great valley. Wondering and admiring, they gazed.

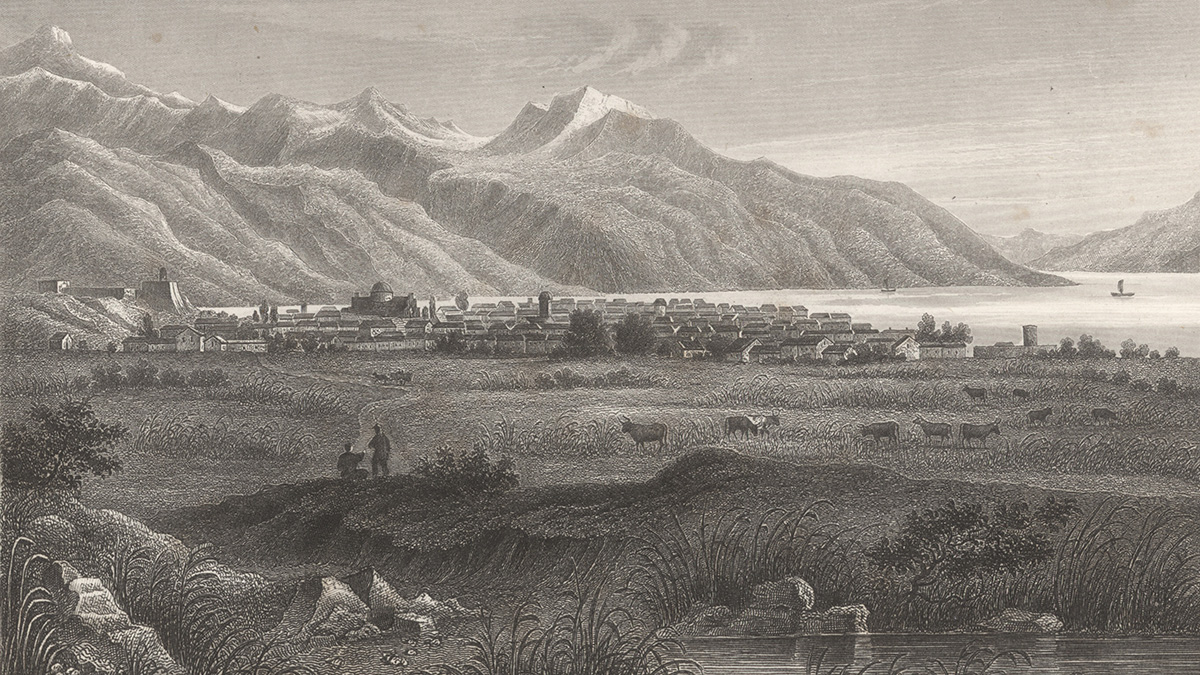

The valley appeared vast and richly fertile, clothed with a heavy garb of green vegetation, adorned in its midst with a large lake from which islands rose, and entirely surrounded with a perfect chain of everlasting hills, mountains covered with eternal snow, and innumerable peaks like pyramids towering towards heaven. It was perhaps the grandest and most sublime scenery in the world.

Their minds reviewed the hard journey from Winter Quarters of 1200 miles through the flats of Platte River, up the steeps of the Black Hills, and into the Rocky Mountains. After the burning sands of the eternal sage regions and willow swales and rocky canyons and stubs and stones, their hearts were glad to gaze on the valley.

Thoughts and pleasing meditations ran in rapid succession through their minds. Sporting trout and other fish would animate the springs, rivulets, creeks, brooks, and rivers of various sizes flowing into the glorious valley and wending their way to the lake. There would soon be orchards, vineyards, gardens, and fields. They contemplated the prophecies: a land of promise held in reserve by the hand of God, a resting place for the Saints on which a portion of Zion would be built, a temple established as the highest of the mountains, and a banner for the distant nations.

On this morning of 24 July 2014, a group of Mormons, including some of my own friends and acquaintances, gathered to Salt Lake City for a mass resignation from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although their specific reasons are diverse, they claim a common theme: if Kate Kelly is not welcome then, they feel, they are not welcome.

Some share Kate’s concern with the role of women in the Church. Some have analogous concerns, such as with the Church’s present and past teachings about gays and blacks. Some have related concerns, such as with recurrent tension between various Church leaders and “intellectuals.” Some have tangential concerns, such as with discrepancies between history as often taught in Church settings and as revealed by careful review of records.

Of course none of these concerns is unprecedented. But they do appear to be reinvigorated. In recent weeks, I’ve observed and received more than the usual number of messages, public and private, expressing angry or tired disillusionment, and repeating bewildered questions. I’ve also observed more than the usual number of sanctimonious responses to those expressions and questions.

I’m not a Mormon apologist. Those looking for someone that would attempt to explain away every uncomfortable aspect of Mormonism in a positive light are looking in the wrong place.

In fact, I tend to be as impatient with Mormon apologists as I am with Mormon haters. Both strike me as excessively indiscriminate, even careless, to some extent with matters of truth, and yet more so with matters of goodness and beauty. Whether successfully or not, I aspire to broader mindfulness and deeper heartfulness in my assessment of Mormonism.

I was born to and raised by Mormon parents, and was baptized, ordained, missioned, and married at the usual times and places. That’s why I’m a Mormon, apparently.

Though really, I like to think I’m a Mormon because I want to be a child of God and a disciple of Christ. I trust we can become like God, far more creative than we now are. I suspect we can do that only if we become like Christ, far more compassionate than we now are. I feel a deep attachment to and motivation from the core principles and esthetics of the Gospel of Christ as interpreted in the Mormon religion.

And the Church generally helps my family and me better understand, feel, and live that Gospel. As a member of the Church, I’ve served as an auxiliary administrator, teacher, financial administrator, scout leader, and representative. Experience in each of these roles has strengthened my trust in our ability to reconcile with each other and work together to make a better world, a heaven on Earth like prophets and scriptures have described. I try to live my faith in practical ways, thinking and feeling with whatever wisdom and inspiration I might have, and then acting with whatever tools are at hand.

While the sublime esthetic that I sense in Mormonism provokes me emotionally, it also demands rationality of me. This has led to some distress.

As a teenager, I felt accumulating tension whenever someone would claim to “know the Church is true” for reasons that appeared to be no more than emotional. As a young adult, I experimented with prioritizing such emotions above the rational, as a way of psychologically managing disillusionment with some interpretations of Mormonism that are plainly inconsistent with history and science. But that only made the tension worse.

Over time, I settled into an integrative work, trusting that the emotional and the rational would prove complementary. Without reason, it’s not true. Without emotion, it’s not beautiful. And without either, it’s not good.

This has resulted in disagreements with some fellow Mormons, who reasonably (and yet ironically) interpret aspects of our scriptural and prophetic tradition as marginalizations or rejections of rationality. Yet I contend that the general gist and thrust of Mormonism, and certainly the understanding and motivation it actually gives me, is toward integration of the emotional and the rational in a sublime vision and practically transformative action.

I’ve written before on the value of religion generally, particularly when provocative of and true to a radically flourishing life. And while I’ve found that value manifest to varying degrees in various interpretations of all major religions, none has manifest it to me more clearly, profoundly, and boldly than has Mormonism. Of course it may be only that I’m irredeemably Mormon.

But I believe it’s also more than that. After all, is there any other major religion that explicitly proposes to make Gods and saviors of humanity? That encourages us beyond satisfaction with anything short of the creative and compassionate capacity of God? That interprets Christian discipleship more immersively?

Is there any other major religion that is more advanced in its realization that posthumanity always has been and will be the practical culmination of all pantheons and theologies and forthtellings and posthuman projections? Not that I know of.

How is that manifest in practice? Imperfectly.

When I visit Welfare Square, I still find the hungry and the destitute. But I also find a people that is actually dedicating uncommon percentages of its time and resources to pursue a shared vision of a better world beyond present notions of poverty and suffering.

When I visit the Family History Library, I still find the dead and the superstitious. But I also find a people that is actually amassing unparalleled amounts of family history data, which may yet empower us to redeem our dead as surely as anything in our world can.

When I visit the Mission Training Center, I still find the naive and the disingenuous. But I also find a people that is unusually committed to engaging in the world, not from the safety of secular superficiality or misrecognized objectivity, but at risk of deeply interpersonal forays into values, meanings, and purposes.

When I visit my local congregation, I still find the disagreeing and the disagreeable. But I also find an opportunity to reconcile with my people, perhaps to raise each other together and become that which we aspire to be.

So I wonder, perhaps with you, “To whom shall we go?” And it seems that the answer is as ancient as it is new. “You have the words of eternal life.”

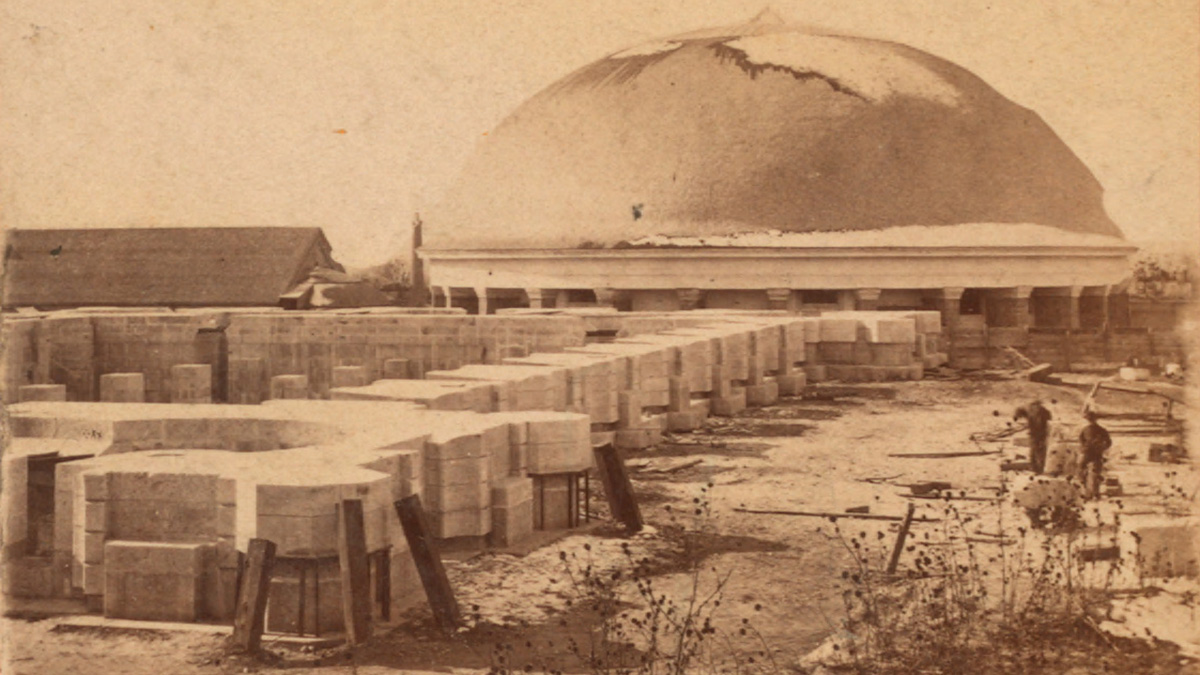

A fevered voice interrupted their contemplation. It expressed full satisfaction in the appearance of the valley as a resting place for the Saints and as ample repayment for the journey. “This is the right place. Drive on.”

After gazing a while longer on the scenery, they traveled into the valley four miles to an encampment that had arrived two days before. On the banks of two small streams of pure water, the encampment had already commenced plowing. And having broken about five acres of ground, it had already begun planting potatoes.